By LEE PACE

Pete Dye remembers playing a practice round for the North and South Amateur in the mid-1940s and encountering two older gentlemen strolling the No. 2 course and talking to some of the competitors. One of the men was J.C. Penney, the department store magnate. The other was Donald Ross, the golf course architect.

“After the round, we were in the bar and everyone was excited about having met J.C. Penney,” Dye says. “I can’t remember a single person thinking it was special he’d met Donald Ross. That’s hard to believe looking back.”

Dye and his wife and golf design partner Alice go way back in Pinehurst.

Pete was a soldier during World War II and was stationed at Fort Bragg in nearby Fayetteville.

Pete Dye at Pinehurst in the 1990s.

“The lieutenant colonel was an avid golfer and had a car,” Dye says. “It was a lot easier to come over here and play golf for three bucks than stay on the base and do KP duty. I had the greatest time coming over here. I’ve played that golf course more than the law should allow. I’ve looked at that thing ’till I’m blind.”

Alice O’Neal was a noted amateur golfer from Indianapolis and met Dye at Rollins College in 1946. Alice played many of the top amateur tournaments and was a regular in the Women’s North and South Amateur (and would win it in 1968). During those competitions, she developed a lifelong friendship with Richard Tufts, the president of Pinehurst Inc. and a noted golf administrator.

“Mr. Tufts was the spirit of everything good in golf,” Alice says. “He really was. He was the spirit of good sportsmanship. His portrait hung on the far wall in the clubhouse. Every time you walked in you stopped and looked at it. It was like a picture of Lincoln or something. You looked at it with a sense of awe. The kind of man he was inspired that feeling in you.”

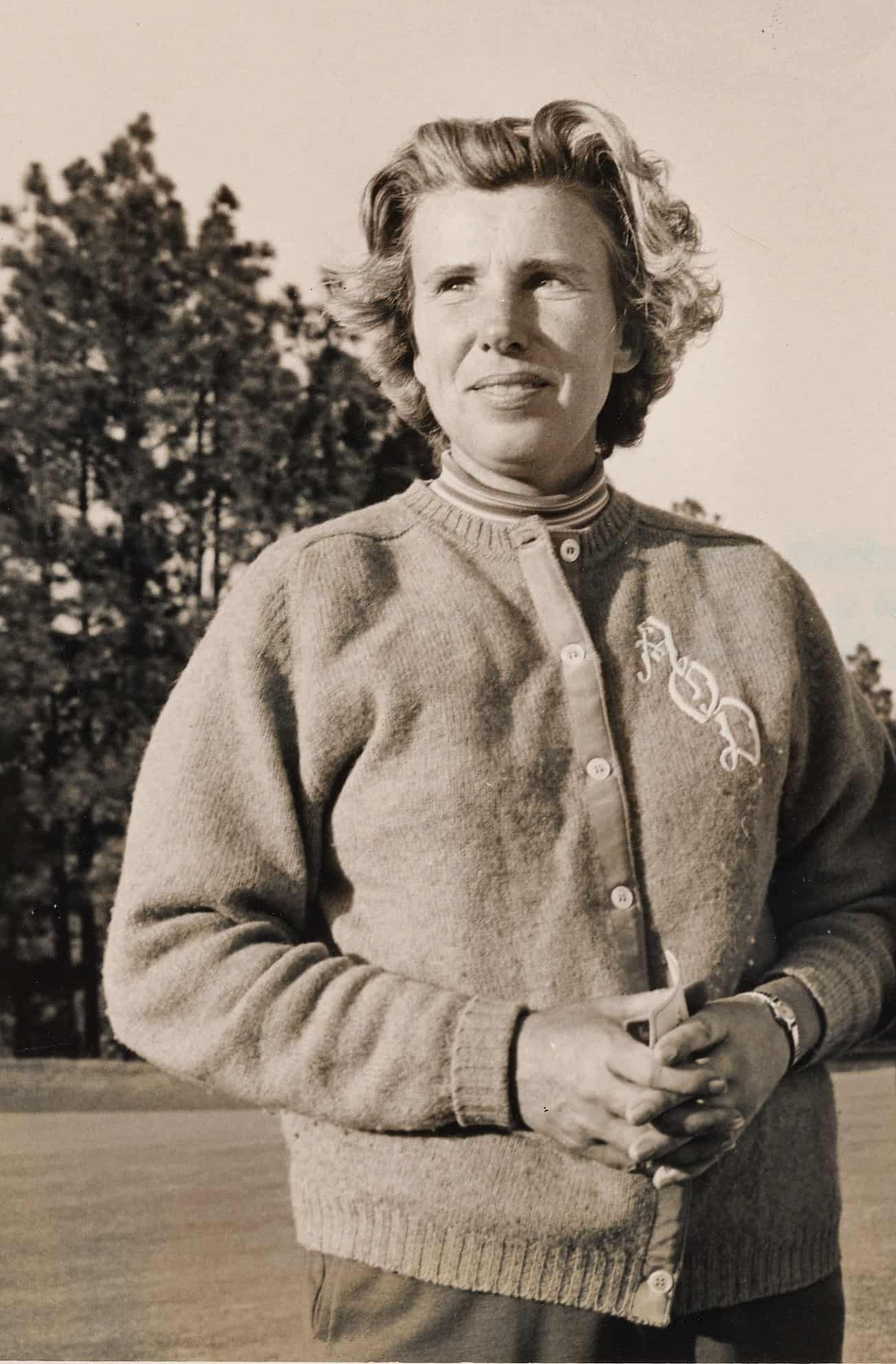

Alice Dye at Pinehurst in the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of the Tufts Archives.)

The Dyes were married in 1950 and Pete began working in the life-insurance business. Both remained avid golfers and enjoyed talking about the art of designing courses, thinking perhaps it might be fun to design a course themselves one day. Tufts played a role in launching what would become one of the game’s most notable design careers.

First, he encouraged the Dyes to visit the great classic courses of Scotland. Pete entered the 1963 British Amateur, and he and Alice tied that trip into a whirlwind tour of some 30 courses—including St. Andrews, Dornoch, Turnberry, Prestwick and Carnoustie.

“On the airplane to Scotland, I sat with Mr. Tufts,” Dye says in his book Bury Me in a Pot Bunker. “He was an austere man who loved golf more than life itself. Armed with a keen sense of tradition, he provided me with an abbreviated history lesson of the legendary courses there.

“Since I greatly respected Mr. Tufts’ opinion, I listened with strong interest. He vividly described intriguing courses that I had only seen in pictures, and his colorful stories only heightened my interest in visiting the home of golf course architecture.”

Several years later, the Dyes designed their first course, a track south of Indianapolis called Eldorado.

“It was very amateurish,” Alice remembers. “There was a creek that ran through the property, and I drew these holes. We had it put on a Christmas card and sent it out. Mr. Tufts wrote back to say how delighted he was to hear we’re going into golf design, that we’d do a great job, that we’d be a credit to the game, that kind of thing.

“Then he said, ‘Don’t you think that crossing the creek 13 times in nine holes is a little too much?’”

Alice Dye won the 1968 North and South Women’s Amateur at Pinehurst in 1968. He name is listed on Pinehurst’s Perpetual Wall in the style of the time – under her husband’s name.

This history and perspective percolated in Dye’s mind in 1967 when Hilton Head developer Charles Fraser hired him and Jack Nicklaus to design and build Harbour Town Golf Links, the site of the RBC Heritage Classic on the PGA Tour. Fraser had opened two courses on Hilton Head in the early 1960s, both designed by South Carolina-based architect George Cobb, and now wanted to make a splash with a new course on 400 pristine acres on the southwest side of the island along Calibogue Sound.

Dye was driving across the island at the onset of the project and took note of a new course being designed by Robert Trent Jones. He noticed the big machinery carving out long tees, huge bunkers and expansive green sites at Palmetto Dunes and decided to take the opposite tact with Harbour Town.

“The concept of small greens and a low-profile course seeped into my brain,” Dye says. “Too much emphasis was being placed on putting in the game at that time. I wanted to return the art of chipping and pitching to the game.”

The resulting cornucopia of multiple-tee positions, small pot bunkers, “shot-making” greens and sculpted, undulating fairways would be lauded by the world of golf – from resort players to second-home buyers and, most significantly, by competitors in the PGA Tour’s new Heritage Classic, which was launched over Thanksgiving weekend in 1969. Harbour Town was the antithesis of Trent Jones’ testosterone-laden layouts. The greens were small and each shaped differently. Dan Jenkins in Sports Illustrated called it “sort of a Pine Valley in a swamp, a St. Andrews with Spanish Moss, and a Pebble Beach with chitlins.”

“It’s different,” Dye said. “But, then, so was Garbo.”

Soon after, Dye was hired to design a new municipal course in High Point called Oak Hollow. That design caught the attention shortly after it opened of an aspiring young golf architect named Bill Coore, who grew up 35 miles away in Denton, N.C.

“In 1971 every golf course had the Robert Trent Jones Sr. look,” says Coore. “They were the proverbial 7,000-yard-plus championship golf course. What Pete was doing was so different. I was enamored with it. I had no clue who Pete was, but I liked what I saw. Oak Hollow was like Harbour Town. It was based on finesse shots, shorter shots, precision and placement. I was fascinated.”

That attraction spurred Coore to pursue an entry-level job working for Dye on his golf courses and was the first domino to fall in Coore establishing himself with partner Ben Crenshaw as one of the top architects in the game today.

So connect the dots: Ross and Tufts to Dye, Dye to Coore, and then Coore back to Pinehurst in 2010 to masterfully direct the restoration of Pinehurst No. 2. Harbour Town and Hilton Head are in there somewhere as well.

Lee Pace is a regular contributor to the Pinehurst Blog. He latest book, “The Golden Age of Pinehurst—The Rebirth of No. 2,” is available in all retail shops at Pinehurst.